|

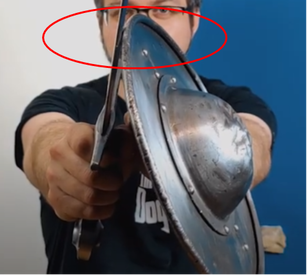

Borislav Krustev posted a video back in 2022 discussing myths in sword and buckler combat that he believes stem from the I.33 manuscript. In today’s post, I will discuss my thoughts on his points. Overall, I believe his critiques come from a point of view that anything not included in I.33 is wrong in the wider context of sword and buckler combat. In general, I believe that many systems with all weapons have their merit and just highlight different points of emphasis for techniques between sources. An Important DisclaimerIn general, I have a tremendous amount of respect for HEMA scholars who present their arguments in polite and professional ways. I have had the opportunity to discuss I.33 with Krustev, and while we do not agree on all things regarding I.33, I respect his opinions and the examples he uses as evidence. I plan to use blog posts like these to spotlight different opinions regarding I.33 to help the reader come to their own conclusions. Krustev’s First Myth: The Correct Sword in I.33 is the Type XIVIn the video, Krustev first argues against the idea that the type XIV is the correct sword for I.33. I agree with Krustev’s assessment that the type XIV sword is not the sword of I.33. As discussed in my post analyzing the different swords that could have been used in I.33, several different typologies could be featured in the art. To Krustev’s point, these terminologies are modern and not what was used in the early 14th century. I have heard some I.33 scholars claim that the type XIV is the best type of arming sword for the I.33 system because the broad shape and shorter blade effectively allow for binding and attacks from the bind. While I enjoy using a type XIV when training, it is not the only type of arming sword for the system. I have used type XV swords and type XVI swords as well and have not found the techniques to be impacted. The ability to execute I.33 techniques with a given sword is subjective to the fencer and even with historical examples, there is quite a large variety of options for fencers when studying I.33. Krustev’s Second Myth: Leg Hits are Ineffective and Easy to CounterKrustev’s second sword and buckler myth that he challenges is that leg hits are ineffective and quickly countered. Based on my interpretation of I.33, I do not believe I.33 utilizes leg attacks. The first play of the manuscript advises the fencer not to attack the legs. Later, in the ninth play, an attack to the right or left can be performed, but the target is not specified. In practice, these could be leg attacks in I.33, but this is not definitive evidence. However, just because I.33 does not showcase this type of attack does not mean they are ineffective. To that point, I agree with Krustev. Andre Lignitzer and other sword and buckler systems feature leg attacks, which is evidence of their effectiveness. Furthermore, single-handed sword systems without the buckler also include leg attacks. So, even without a buckler, leg attacks are utilized. Given the leg attack being featured in other systems, it does not appear to be easily countered either if set up properly. What I believe is universally true in swordsmanship is the riskiness of leg attacks, particularly as an opening action, as warned against in I.33. Whenever the sword is attacking low, it is not protecting high. The assistance of the buckler may add some risk reduction during this attack, but the risk of doubling or just being hit outright is still a concern. Perhaps the minds behind I.33 were so concerned with this risk that they chose to opt out of this attack entirely when attacking. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of the leg attack is perfectly valid, albeit risky, as Krustev also states. Krustev’s Third Myth: The Buckler is Covering the Sword HandIn his last point, Krustev challenges the idea that the buckler needs to cover the sword hand. He particularly focuses on the flattening of the buckler while the hands are practically touching. I agree with him to the point that having the sword and buckler hands separate is an effective fighting style. After all, according to I.33, all fencers use the seven common wards, which implies that those positions can be fought from effectively. Krustev also highlights that it is true that when the buckler is extended forward, the buckler does protect the hand. Where Krustev and I begin to diverge is in the use of the sword and buckler hands close together and the flattening of the buckler. In I.33, the techniques intend to have the sword and buckler hands nearly touching, practically wrist to wrist. To do this, the buckler does flatten. Krustev argues that there is a more effective position where the buckler is slightly angled forward and to the side that covers the hands than flattening the buckler commonly seen by I.33 scholars. However, I would argue that the more critical area of coverage and contact point is where the buckler touches the blade of the sword, shown below: The main reason for this is that during binding actions, generally the sword is angled forward into longpoint, not perfectly vertical as shown in halfshield. This means that the contact point highlighted above is facing the opponent and covering areas a sword may slide down during the bind. The idea that this position while in halfshield does not protect the hand is even discussed in the manuscript. I.33 includes a play where a common fencer believes they can separate the sword and buckler of the I.33 fencer's hands while in halfshield. The counter to this strong cut is to turn the sword and buckler hands, then enter with an attack similar to a parry and a riposte. I believe this play highlights how the sword is still the primary offense and defense while the buckler is primarily focused on allowing the sword to stay extended. The fact that halfshield starts with the hand more exposed with a flattened buckler is more to set up the following actions than it is to protect the hands. Now with that said, the position where the buckler is flat towards the opponent does appear in the Cluny Fechtbuch as shown in the example below: If the Cluny Fechtbuch is illustrating the Andre Lignitzer plays, then it is reasonable to assume that the buckler facing forward as during binding actions Krustev describes is valid from a historical perspective. While I do not believe I.33 uses this positioning, I believe that both are valid and used to support different techniques with the sword. Closing ThoughtsI believe Krustev’s biggest criticism of I.33 is that it does not include techniques from other systems. If taken to the extreme, I.33 scholars may make the mistake of thinking that only the techniques of I.33 are effective, even if other systems state the contrary. In swordsmanship, the end goal is to hit the opponent without getting hit. If you do an action that is not explicitly in the source you study, but you hit the opponent without getting hit, you did something right.

Given the source material of I.33, I cannot say definitely that the minds behind the manuscript would advise fencers to attack the legs or to attack with the sword and buckler separately. Nevertheless, these are essential parts of generic sword and buckler combat and likely something the authors of I.33 had to consider when making their manuscript. I have my opinions on what I believe I.33 would do to counter those techniques, but that is a story for another day. And with that, I would like to thank Borislav Krustev for taking the time to create his video. Commentaries like this are important when HEMA scholars compare and discuss techniques and different sources. It is no secret that I am a fan of the techniques of I.33, but it is important to listen to the critics of the systems to find potential gaps or vulnerabilities. Through their critiques, we can all move towards refining our interpretations and moving closer to correctly interpreting the sources.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Proudly powered by Weebly